Mental health challenges of refugees in Germany during the covid-19 pandemic.

This article explores the effects of the pandemic on the mental health of refugees in Germany, based on three case studies from Berlin, Friedland and Hamm. It draws attention to the ongoing conflicts and protracted situations for refugees and asylum seekers at the borders of Europe and in reception centres within the EU.

Magdalena Böhm (Mind Refuge), Mainz (Germany),

A lot has been said about mental health consequences such as increased rates of depression, anxiety and insomnia resulting from experiences during the covid-19 pandemic in Europe and beyond (Prati & Mancini, 2021). Lesser attention has been paid to ongoing conflicts and protracted situations for refugees and asylum seekers at the borders of Europe and in reception centres within the union. This article explores the effects of the pandemic on the mental health of refugees in Germany, based on three case studies from Berlin, Friedland and Hamm.

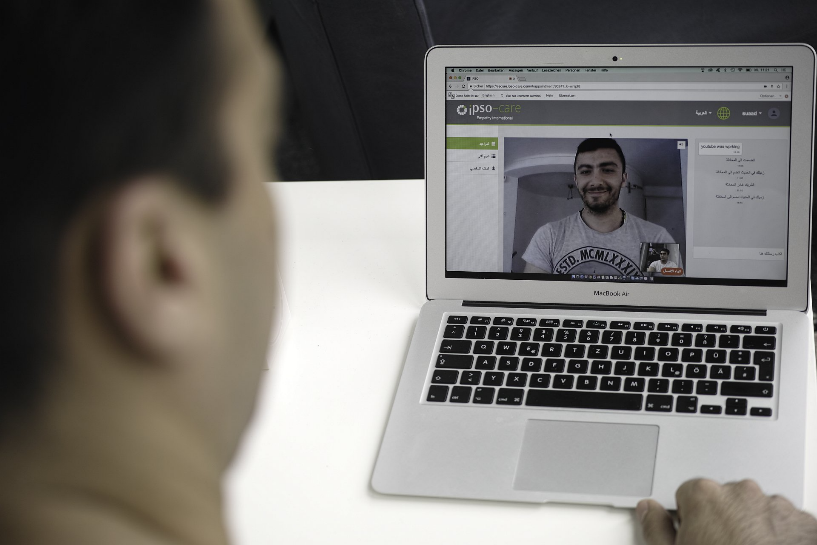

Ahmad Chahabi is a psychosocial counsellor at the International Psychosocial Organisation (Ipso). Ipso is a humanitarian non-profit organisation based in Germany and Afghanistan specializing in Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Services (MHPSS) and providing easily accessible and culturally sensitive psychosocial counselling face-to-face and online.

Since a few weeks Ahmad is again allowed to pay visits to reception centres in Berlin on a weekly basis, a support service that has stopped during the pandemic – as many other health and integration measures for refugees. He could re-enter the reception centres only after Berlin had to witness three suicides within one week in March 2021. “Never heard of before”, he comments. An alarming number that highlights the severeness of mental health challenges for refugees and asylum seekers during these times of the pandemic.

Facing uncertainty

Ahmad is an expert with lived experience coming from Syria and arriving to Germany 2015, he remembers clearly what life in a reception centre in Berlin was like. “The reception centre”, he says “is this first save place that we are in but it’s not what we want. Refugees have high expectations. They don’t identify with the centre. It tells you, you are still in a process, still a refugee but that there is a prospect that one day you can leave. But now in times of covid-19, they have to stay there but for how long? It is unknown.” He explained that many processes like asylum decisions and family reunification have slowed down or stopped since the outbreak of the pandemic, leaving people and their families in a place of uncertainty, not knowing if and when they will be able to truly enter society or join with their loved ones. This state of not knowing has precarious effects on refugees’ mental health as it diminishes their motivation, hopes and plans for a future in Germany.

There is increased fear, he continues, in every persons’ eyes these days, including us who live here longer but for refugees and asylum seekers this fear is heightened because instability reawakens the thoughts and feelings they have had back home where things were unpredictable and instable too. Based on their history, refugees may interpret the current situation as if the solid ground they have found in Germany is now shaking suggesting that they are not save anymore. These are memories but although their current circumstances might be different, they feel very real. Ahmad explains that rationalizing and explaining that this association is what is causing these feelings of insecurity can often help a long way.

In Hamm, refugee counsellor Linda Voß works for the local non-profit organisation Caritas Hamm. She confirms that many of the processes refugees arriving to the city need to complete, take a lot longer than before the pandemic. Linda’s clients have great interested in completing their documentation for family reunification but as she is only allowed to schedule appointments for urgencies that have strict deadlines, since a year, she is not able to help clients in this matter. To add to the problem, as responsible embassies worked temporarily in emergency mode during the pandemic, family reunification processes have slowed down considerably, she explains.

Limited access to integration support

In general, a lot of integration support has stopped or moved to the digital space, Linda explains. We cannot offer a consultation-hour anymore where people could just drop in and receive help with their questions. Now clients need to call or email which is an additional barrier as they may feel insecure about their language- or IT skills. “A lot of authorities are closed too”, she continues “there is an increased need for support, clients bring much more mailed letters than before.” In the past, her clients would visit the sender of the mail directly and address the inquiry there on-site, now she helps them answer the mail.

Beside their administrative needs, due to health protective measures, refugees miss out on opportunities for social inclusion as all local initiatives like cultural gatherings, sport clubs and any other social activities have stopped.

Personal challenges, IT skills and literacy

Eva is a Policy Officer for Resettlement and Refugee Counsellor at Caritas in the refugee and migrant transit centre in Friedland. The centre receives repatriates, asylum seekers and refugees that arrive to Germany through international protection programmes, such as resettlement.

“Asylum seekers in Friedland”, she explains “receive from us the same integration support as before but now through digital channels. Language courses, information sessions have all moved to the digital space”. It took some clients a lot of getting used to this new situation, she explains. There are huge individual differences regarding people’s ability to navigate these new online offers. Of course, some clients have had professional experiences with conferences calls in the past, but for most, web meetings are something completely new. From her experience, meeting online can work if staff is able to explain to clients in person how these apps work and if the internet connection in the centre is stable enough. But that is not always a given. And the illiterate or older generations often admit that they are not able to understand how to use these tools, she adds.

“In my work,” Ahmad explains, “I always have to consider individual capacities and most refugees do need a lot of guidance nowadays when it comes to legal and administrative processes as they are not used to doing things online.” He reports of clients who feel overwhelmed when needing to renew their residence or work permits online and risk expiration of their documents while they are waiting too long for appointments to handle the issue in person as they were used to and know how to do.

Lacking infrastructure

In addition to personal barriers, the infrastructure often impedes asylum seekers from attending virtual integration offers. Refugees often do not have the devices and even if, the Wi-Fi connection in reception centres is generally poor, comments Ahmad. Eva reports of similar problems in Friedland, the kind donation of tablets to the transit centre from the federal state last year, could not show expected results as online meeting applications require a strong and stable internet connection and could therefore not be used for its original purpose to connect refugees live and online to integration offers.

Experiences of isolation and conflict

Refugees who come to Friedland through humanitarian admission programmes, enter a ten day quarantine immediately after arrival, followed by a corona test on the last day. If the test is positive, the refugees need to stay quarantined for another 14 days. These weeks of isolations are very burdening for the newcomers, explains Eva. “This groups suffers the most under the pandemic.” Caritas staff cannot go see them, even not through the window from the distance and are only in contact with the families through email, messengers or online calls. Many refugees travel as a family unit and are then quarantined all together in a single room leading to conflicts on a regular basis.

“This is the main topic, I would say”, Eva continues “the conflicts between family members who share a small space for weeks in isolation. We had several instances of men and women reporting domestic violence to us.” Equally, Linda explains that clients report an increase in conflicts between asylum seekers in the reception centres in Hamm, likely caused by the perceived instability and unpredictability of the current situation. Ahmad explains that hard lockdowns during which refugees were not allowed to leave the centre led to more family conflicts and domestic violence as family members have to constantly face each other and everyone’s worries about the future. His clients reported feeling alone and isolated as a family. A similar situation in Hamm, particularly for families that have left the centre and live in individual housing, feel left alone and in need of contact to others including the local population, reports Linda.

Health concerns

Refugees are less worried about their own health than about the health of their family members, particularly if those are still back home or in neighbouring countries where medical care is less available, says Linda. Ahmad admits that many of his clients are not aware how dangerous the covid-19 virus could be for their health as they see their own wellbeing as a second priority. Eva reports that some see the situation as a serious risk to their loved ones therefore avoid contacts and prefer managing administrative inquiries online.

Job insecurity

Since the outbreak of the pandemic and its effect on the economy, refugees and asylum seekers have increased worries regarding securing and retaining employment opportunities. Many have lost their job, reports Linda and now little chance in finding a new one as important sectors such as the service industry, stopped hiring. This situation is severely impacting refugees’ mental health, Linda continues, several clients started developing psychological problems after losing their job. “Particularly insomnia and anxiety are often reported to me”, she says.

Clients are either anxious about losing their job or worry not finding one, explains Ahmad. In addition, they struggle with renewing their work permit online and often risk expiration while waiting for an in-person appointment. This leads to a lot of self-blaming, he notes, as they feel unable to handle procedures online and provide for themselves and their family.

Language, education and status insecurity

When social distancing was introduced, in some cities, language and integration courses continued classes online. In Hamm, existing classes resumed online but new courses for newcomers could not start as new pedagogical concepts for online learning needed to be developed and newcomers are unable to do a level test in the current situation. As a result, until recently no new language courses could start since the beginning of the pandemic. “This is a real problem”, explains Linda “there is huge motivation to learn the language, but new arrivals are not able to start”. Refugees who live in Hamm for a while now worry about losing their language skills as they are not able to see anybody besides their family members. They often express their wish to have contact with Germans again, she adds.

To the refugee and migrant transit centre in Friedland, repatriates, resettled refugee and asylum seeker arrive before they are assigned and transferred to a municipality in Germany. Since the start of the pandemic, “all our newcomers are anxious about not being able to learn the language”, Eva explains. Except a few examples who are able to learn independently using the internet, most clients are very concerned when they learn that they cannot attend language classes in their municipality. “In some cities these courses have been replaced by online learning but that is not always the case, there are regional differences”, she adds.

Ahmad’s clients in Berlin have the opportunity to attend online language classes but in practice, the poor internet connection in the reception centre often prevents them from accessing these online meetings. Others report not being able to concentrate in a room with five roommates who they worry not to disturb.

Parents have additional concerns, as they worry how their children will be able to learn and make friends during online schooling. The same struggles with poor internet connection in reception centres applies to home schooling, says Ahmad. In addition, parents are often not able to support their children’s home schooling as it is currently expected due to their unfamiliarity with the topic of the lessons, lacking language- or IT skills.

Attendance and completion of language, integration classes and child schooling are preconditions for residency and status renewal. Therefore, concerns about not being able to advance in language proficiency provoke fears of having to return and not being able to stay save. Many refugees are much aware of this potential link of events, Eva confirms.

Positive learning

“For refugees who are already autonomous, this new situation really revealed their capacity to me”, says Linda. Her clients were able to adapt quickly and send documents via email just for Linda to review them instead of passing by and having her help to fill them in from scratch as they would usually do in the past. “I realised that we have sometimes underestimated their self-sufficiency”, she adds.

Covid-19 led many to understand what is truly necessary in the process of arriving and settling. Ahmad reports that little things who were taken for granted are now more appreciated after they have been removed, such as the opportunity to attend a language course or meet someone outside of the centre.

Refugees have high expectations of Germany, says Eva and even if they would get the illness, they feel save and taken care of here. “They are generally all very grateful to be in Germany during these instable times.”

Women

“Before corona, we ran a women’s café where women from different backgrounds and walks of life would meet, exchange and initiate projects”, Linda explains. Her clients miss this space and time for themselves. Since home schooling was introduced as a health protective measure, often the whole family is at home leaving little time and space for mothers to take care of themselves or follow their aspirations. Their dreams and goals tend to be forgotten, Linda adds, but their pursuit would be important for women’s wellbeing and inclusion.

In all three locations, interviewees are concerned that the most vulnerable will “fall through the cracks” during this time of limited service accessibility as this group is most effected by social isolation, economic instability and health hazards but the least likely to initiate contact and ask for help using phone or email.

Finding purpose

Ahmad explains that for his clients, the vison of the future has been blurred as they simply cannot plan their future in Germany these days. This makes them forget their resources, lets them feel lost and overwhelmed. It is another stressful situation after all they have already been through and may seem contradictory to the purpose of why they chose to flee to a save country.

Linda explains that several of her clients are demotivated as all of their plans and prospects in Germany have fallen apart. Everyone seems tense, nobody knows how things will continue. “As for us citizens”, she says “the future perspective is not clear anymore.” Just that refugees and asylum seekers face additional challenges like traumatic memories of the past, language barriers, unfamiliarity with system and procedures, discrimination, lack of social networks etc. Her clients struggle finding purpose, they want to have a reason to get up in the morning she explains, instead of waiting for their asylum process to be completed. “Even volunteering is currently not possible”, she adds, the pandemic has really worsened their lookout on life and ability to contribute to society.

“What is lacking, is a bit of everyday life”, Linda concludes, sitting in a café with locals and daring to order a coffee in German thereby getting the chance that these everyday experiences become familiar, the new normal. That is the main issue, she says, the everyday life is not present, and yet again, all structures that they knew have fallen apart.

References:

Caritasstelle im Grenzdurchgangslager Friedland: http://caritasfriedland.de/landesaufnahmebehorde/

Caritas Hamm: https://www.caritas-hamm.de/beratung-amp-hilfe/migration-und-integration/beratung-fuer-fluechtlinge/beratung-fuer-fluechtlinge

Ipso Context: https://ipsocontext.org/about-us/

Prati, G., & Mancini, A. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 51(2), 201-211. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/psychological-impact-of-covid19-pandemic-lockdowns-a-review-and-metaanalysis-of-longitudinal-studies-and-natural-experiments/04BBA90C535107A90B851DFCE8D4693C

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5

Wang, Y., Shi, L., Que, J. et al. The impact of quarantine on mental health status among general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mol Psychiatry (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01019-y